By definition a Mortgage Servicing Right, herein referred to as MSR(s), is a contractual agreement where the right, or rights, to service an existing mortgage are sold by the original lender to another party who, for a fee, performs the various functions required to service mortgages. As a servicer, firms are responsible for collecting borrower payments including Principal and Interest as well as Taxes and Insurance, and then remitting those payments to investors, insurance companies, and, if applicable, taxing authorities. If a borrower is late with their payments, it is the servicers responsibility to do everything they can to collect payments and, if necessary, late fees from the borrower. If a borrower fails to make their payments after a prolonged period of time, usually 120 days or more, and if all efforts fail to bring the borrowers current in their payments, servicers must initiate foreclosure and ultimately, liquidate the delinquent accounts. Servicers are also responsible for reporting to investors about the status of their investments and they may be required to advance funds to investors and/or taxing authorities whether the borrower makes their payments or not. Last but not least, servicers must handle all customer and investor questions and requests, and record a satisfaction of mortgage at payoff.

- The accounting and reporting for mortgage servicing assets as set forth in FASB ASC 860- 50. FASB ASC paragraph 860-50-25-1 requires that an entity recognize a servicing asset or servicing liability each time it enters into a servicing obligation which may be qualified as follows:

-

If meeting the requirements for sale accounting, a servicer’s transfer of any of the following

-

an entire financial asset,

-

a group of entire financial assets,

-

a participating interest in an entire financial asset, in which circumstance the transferor shall recognize a servicing asset or a servicing liability only related to the participating interest sold

-

-

An acquisition or assumption of a servicing obligation that does not relate to financial assets of the servicer or its consolidated affiliates.

After a loan is sold, assuming the servicing has been retained, the MSR should be capitalized at fair value and subsequently accounted for using either the Amortization or Fair Value method. When the MSR is initially capitalized, an asset is recorded to the balance sheet and income is recorded for the full fair value of the asset.

When accounting for MSRs, the fair value of the asset is best determined by observing actual trade levels for similar assets, though actual trade benchmarks can be difficult to obtain. Assuming permissible market conditions and a willing pool of buyers and sellers, MSRs can be a liquid asset, but obtaining the exact execution level negotiated between two private entities can be problematic. As a result, the most commonly used method for determining the fair value of MSRs typically involves a combination of observed and unobserved assumptions. MSRs may be valued on a loan level basis or stratified into tranches of like portfolio characteristics, but regardless of your approach, MSRs can still be a challenging asset to value. Conventional wisdom might suggest that if it cost $125 annually for a firm to service a single MSR then $125 should be the model assumption used when deriving the assets value. Perhaps, that would be the case if fair market buyers were also using $125 as their annual lifetime cost to service estimate, but therein lies the problem! No two firms are created equal when comparing economies of scale, cost of funds, or as one of many examples, their access to cost reducing technology. While it may cost one firm $125 annually to service a MSR, a buyer with more preferential economies of scale may be willing to pass part of their economic benefit to the seller by agreeing to pay a price that takes into consideration a more preferential cost of servicing. Other key behavioral assumptions used in estimating the net present value of future servicing income are prepayment speeds, discount rates, and delinquency rates. On the revenue side, firms may include items such as contractual service fees, ancillary income (bounced check fees, pay by phone fees, etc.…), late fees, and float income.

With no combined shortage of assumptions that go into deriving the underlying MSR value, considerable judgment is required. Being off on just one assumption could materially affect the estimated fair value of the servicing rights.

Amortization Method

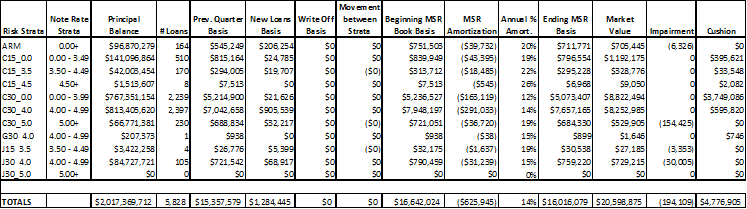

After initially recoding MSRs at fair value, when utilizing the amortization method, commonly referred to as LOCOM or Lower of Cost or Market, MSRs are amortized over the estimated economic life of the mortgage in proportion to the anticipated future net servicing revenue generated from servicing the loan. Over or under amortization is a problem routinely encountered when amortizing MSRs. Ideally the length or term of the amortization should coincide with the Economic Useful Life of the MSR asset. Those who choose to amortize their book value utilizing a straight line amortization technique may fall victim to market fluctuations that can extend or shorten the projected life of a given asset. This is due to fluctuations in primary mortgage rates which may cause a shift in the “In-the-Moneyness”. “In-the-Moneyness” refers to a MSR asset or group of MSR assets that, due to a shift in primary mortgage rates, may now have a greater incentive to refinance, thereby increasing projected prepay projections and shortening the projected economic life of the asset. For clarification, prevailing mortgage rates may move in either direction, but if a firm is not proactive in recalibrating the rate of amortization, they may be at greater risk of either over amortization or impairment. MSRs should be evaluated for impairment on a continual basis or, depending on the size of a firm’s MSR asset relative to their total net worth, at least every reporting period. MSRs are to be grouped into homogenous risk buckets with the most common breakouts being Product, Term, Note Rate range, and sometimes geography. Impairment occurs when the remaining book value, net of accumulated amortization, is carried at an amount that is greater than the estimated fair market value of the servicing right. In instances where the unamortized book value exceeds the estimated fair market value, a valuation allowance must be recorded to bring the asset down to fair market value. Unless determined that the asset is permanently impaired, in which case a permanent correction may be necessary, the previously impaired asset can be recovered and the valuation allowance reduced through a recovery to earnings often related to a rise in primary mortgage rates which may serve to increase the projected economic life of the asset. This recovery cannot be in excess of the previous impairment, meaning that under the amortization method, it is not permissible to record value in excess of a firm’s remaining book value net of amortization. If not already impaired, the amortization method can result in less volatility in earnings and lessen the need or desire to hedge potential volatility because any cushion at the homogenous risk cohort level, while not recordable, can serve as a first line of defense to protect against any volatility created by a downward shift in primary mortgage rates. As illustrated below, an impairment test can look as follows, but be advised that risk stratum must be maintained over time. For instance, just because a particular set of risk buckets are appropriate today, does not mean that this holds true indefinitely. Risk tranches need periodic reevaluation to account for increased product diversity and/or any significant change in primary mortgage rates which may relegate virtually all new originations into a single risk stratum. Be advised that auditors may frown on any embarrassment of riches derived from a shift in risk stratum, but it is equally unadvisable to relegate 95% of firm’s assets into a single risk tranche. This can easily occur when a shift in market rates produces a scenario where certain risk tranches are not populated with new production due to a shift in primary mortgage rates, thereby forcing most, if not all, new loan sales into a limited number of risk strata. Over time this can create an imbalance of risk into a single tranche. If you believe this applies to your current situation, professional advice, including but not limited to, internal and external audit support is advisable.

TABLE 1: MSR Impairment analysis

*Note that the amortization method while often perceived as a more conservative method of managing one’s balance sheet is more complex than alternative options.

Fair Value Measurement Method

To avoid confusion, for accounting purposes, whether choosing the Amortization Method or Fair Value Measurement Method, the initial valuation and recording, plus all future reaffirmation of MSR asset values, should be valued at “Fair Value”. The difference between measurement methods is how changes in asset value are recorded. If choosing the fair value method to account for MSRs, the MSRs are measured at fair value each reporting period. The changes in fair value are recorded to earnings in the period in which the fair value changes occur. Similar to the amortization method, MSRs are evaluated periodically to determine that capitalized Accounting for Mortgage Servicing Rights amounts are not over or under valued, but are consistent with current fair market. Any change in fair value is recorded directly to the MSR asset under the fair value method without the need for a valuation allowance. While the Fair Value Measurement Method can be less burdensome on a firm’s accounting staff, the fair value method will undoubtedly create additional volatility compared to the amortization method largely due to fluctuations in the value having no amortization offset. This means that any change in value will directly affect earnings. The amounts recorded in the balance sheet more closely reflect the true fair value of the asset and will always be greater than, or equal to, the amounts recorded using the amortization method. Aside from positive administrate aspects, this can be especially advantageous in a rising rate environment due to a firm’s ability to recognize the gains associated with any increases in fair market values. Once the fair value method is elected, a company cannot change to the amortization method.

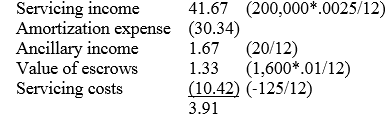

For illustration, what follows is a simplified monthly income statement for a $200,000 loan the month after it is sold. The servicing fee is 25 basis points, the ancillary income is $20.00 per year, the monthly value of the escrow float is estimated to be $1.33 (average escrow balance of $1,600 at 1.00 percent interest), and the servicing costs are $125 per loan. For the sake of illustration, the servicing asset is being amortized under the straight line amortization methodology.

Hedging MSRs

With any fair market asset comes the potential need to hedge what can be a very volatile asset depending on prevailing market conditions. The most effective hedging strategy is to first understand your risk exposure. All too often, firms may not understand the full impact of the changing rate environment, and/or have policies and procedures inadequately covering their MSR Risk Exposure. Once a firm has a quantitative measurement of their risk exposure, the next step is to find the right balance, with a variety of derivatives, to offset the duration, convexity, basis and overall volatility risk. For example, TBAs help to offset duration, but adding additional negative convexity to an already negatively convex asset, can sometimes be too much. Mixing in interest rate swaps will help to offset the negative duration but will have no effect on any basis or Vega risk. Interest Rate Swaptions will provide positive GAMA and Vega, but options can be costly if not properly managed. That’s where specialized models overseen by experienced personnel and/or outside expertise may be necessary.

When deciding on and implementing any hedging strategy (other than a sole reliance on natural hedging), it is important to utilize the same term structure model and prepayment model to ensure the highest correlation. Also, utilizing a retrospective or attribution reporting to decompose the risk and hedge effectiveness is key. With any negatively convex asset, coupled with existing rate volatility, it’s important that one constantly monitor performance to make sure that when rates rise, your firm is not completely squeezed out of all value. Last but not least, hedges may be a costly decision, so before embarking on any risk mitigation strategy, seeking out expert advice can pay dividends.

Pros and Cons of Owning Mortgage Servicing Rights

Before making the decision to own or sell MSRs, it is important to understand how the decision may affect both long and short term earnings. For starters, it is paramount to have a firm understanding of the degree of convexity given current positioning on the “S Curve”. For instance, the lower the note rate relative to current market, changes in market value may become de minimus. Alternatively put, MSR values can hit what may be referred to as a “Glass Ceiling”. Once a portfolio of MSRs note rate is already below current market rates, the incentive to refinance is relatively unchanged between, for instance, 100 basis points and 200 basis points below current market. At that point on the curve, significant upside to MSR value may be attributed to changes in economic earnings rates, and even that may be minimized depending on the remittance structure. Should primary mortgage rates rise, your firm’s upside may be near a point at which additional upside gain in MSR value is limited. For those looking to sell at or near market high’s, whether strategic or need based, they may choose to take advantage of their current position by selling a portion of all their MSR holdings.

Also on the list of considerations is accounting treatment. GAAP requires all MSRs to be initially booked at Fair Market Value (“FMV”). However, firms can choose to maintain FMV on the asset, or use Lower of Cost or Market (“LOCOM”) in subsequent reporting periods. The majority of mortgage firms over the last several years chose to maintain their MSRs on a LOCOM basis. While LOCOM has numerous benefits to those looking to minimize the impact of volatility, one downside is the inability to write the MSR asset value above its existing amortized book basis. A rapid ascent in MSR values may leave many firms unable to take short term advantage of recognizing the upside in value. The quickest and easiest way to recognize the spread between current LOCOM book basis and Fair Market Value is to sell the existing MSRs. As a reminder, firms cannot toggle back and forth between LOCOM and Fair Value accounting treatment, so if there is any hesitation toward migration to Fair Value accounting treatment, selling all or a portion of a firm’s existing MSR portfolio may be the preferred route.

Anyone retaining MSRs today may be subject to changes in the regulatory environment, including but not limited to Basel III, Qualified Mortgage, and Qualified Residential Mortgage. While regulation is often born for the right reasons, the inevitable side effect is almost always increased servicing costs. The already thin margins makes potential increases to servicing difficult to handle for everyone except those with the most preferential economies of scale. Strategic transactions designed to limit one’s exposure to the increased regulatory cost may serve to minimize a firm’s exposure.

When taking into consideration the required accounting treatment, the potential need for impairment testing, amortization, and possible risk volatility mitigation, managing the MSR asset can be complex even for those with sufficient resources. While delegating those responsibilities to a third party is a valid option, others not wanting to manage the complexity of this asset may decide that a sell strategy is in their best interest.

Cons

Selling MSRs today may jeopardize future earnings particularly in a rising rate scenario. As rates rise, the expected life of the MSR asset increases, which can provide a natural hedge during times of decreased originations. Firms may hold the asset to pay off before maturity, or as is oftentimes the case, firms may treat their MSR portfolio as a “Piggy Bank” and only sell on an as-needed basis to accomplish quarterly earnings. Either way, selling MSRs today may mean forgoing potential future revenue streams.

Servicing MSRs can be complex and expensive and may represent significant opportunity cost. Even so, firms may choose a long term retention strategy solely because they don’t want to pass their customer’s to competing firms who may leverage the seller’s client base for cross-sell or recapture opportunities. For those lacking in products, infrastructure, or the resources to cross-sell, selling may be a wise decision. For others, retaining potentially low margin MSRs may be the best long-term decision considering prospective opportunities afforded by a retention strategy.

What Constitutes Fair Market Value

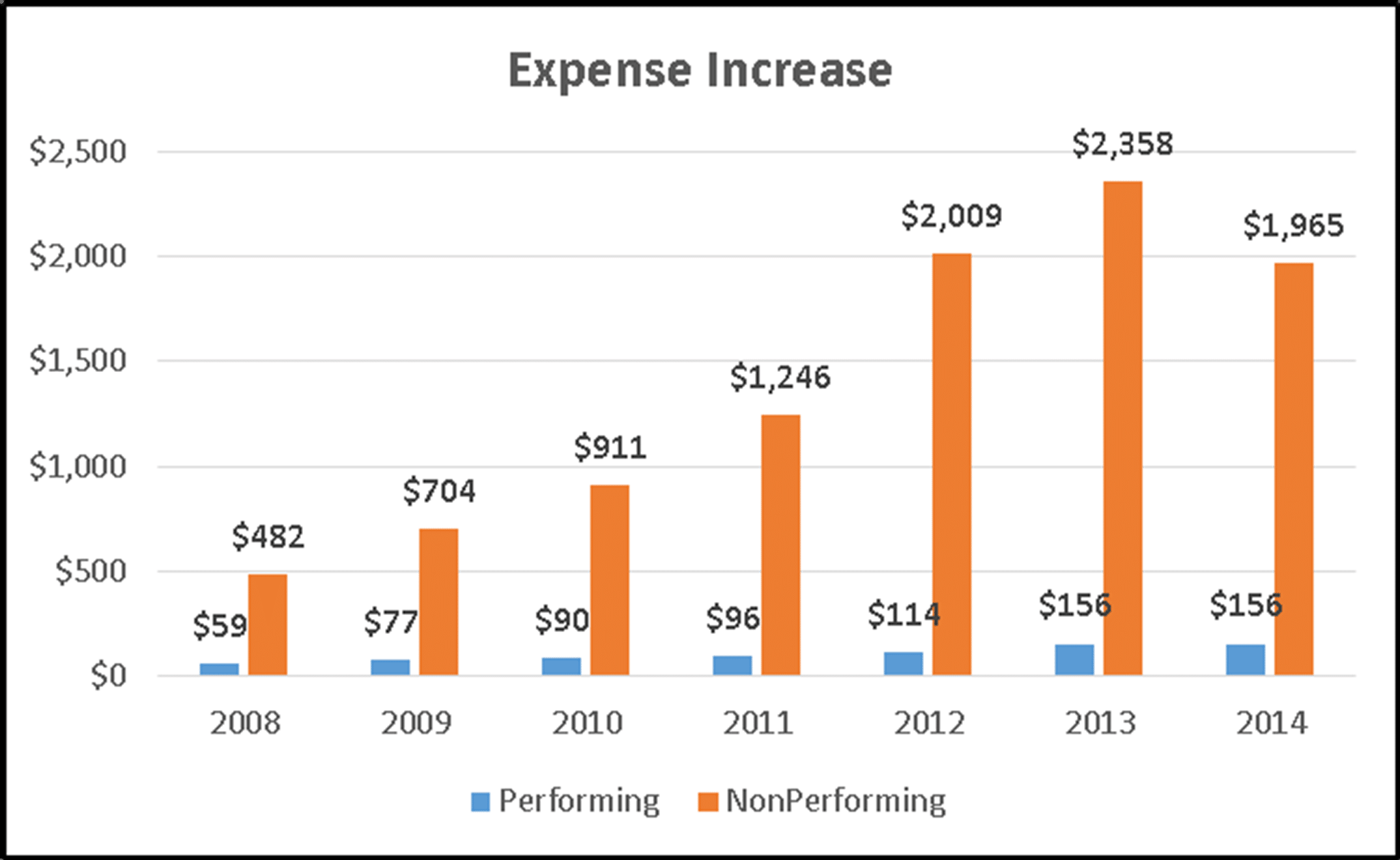

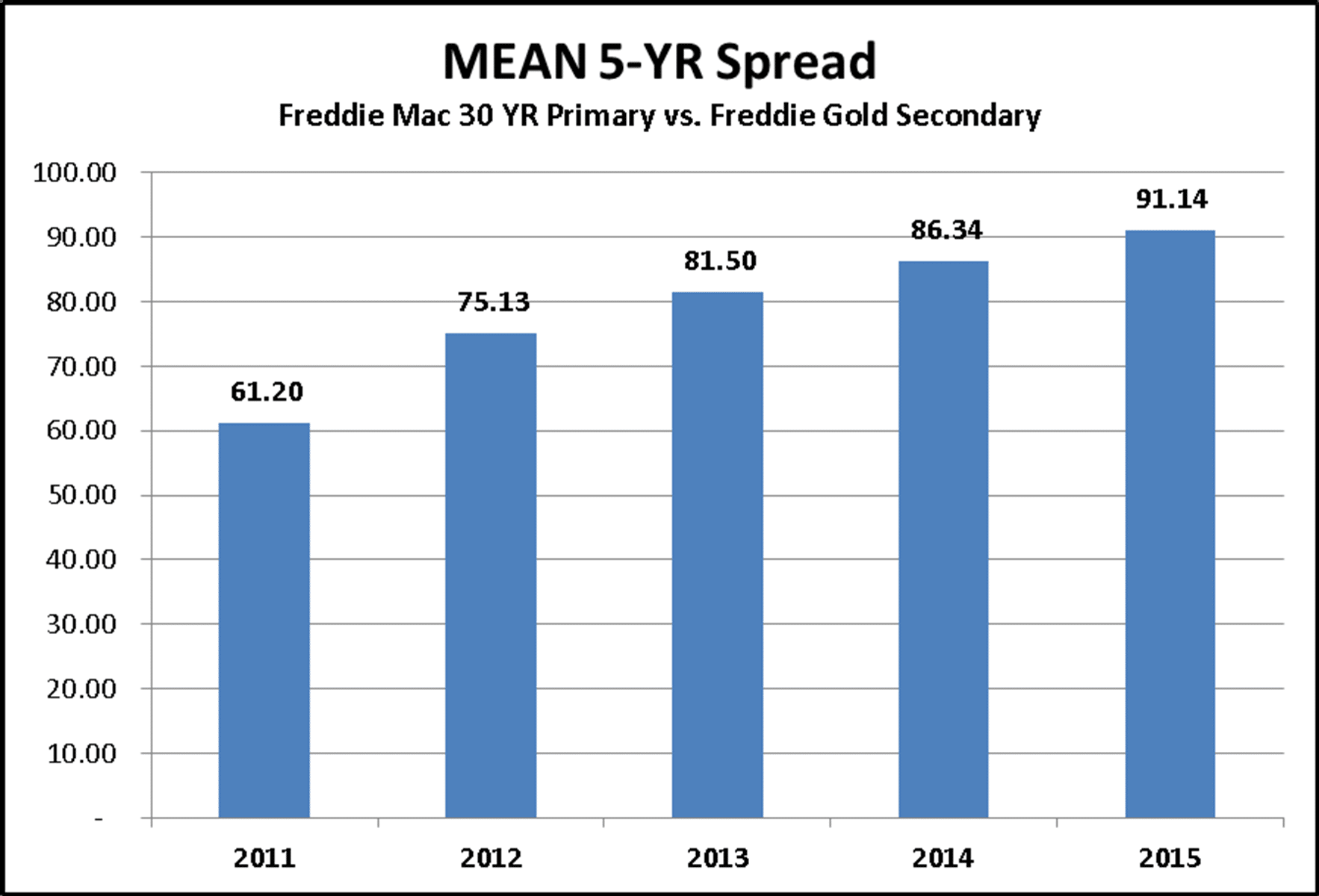

For the long term viability of the mortgage servicing market, it is essential that the regulatory bodies governing this industry strive for greater harmonization if for no other reason than reducing the cost of compliance. For example, in response to rising compliance costs (see Table 1) and decreased servicing values, originators systemically increase margins (see Table 2) by passing higher costs onto the consumer in the form of higher rates which result in improved trading gains.

Table 2: Expense Increase

Table 3: Freddie Mac 30 YR Primary vs. Freddie Gold Secondary

This begs the question, what should be included in a “Fair Market Value” once buyers start paying up for the opportunity to acquire and “Churn” a portfolio. Clearly this strategy only works in a falling rate environment in which borrowers have the incentive to refinance their mortgage. However, with unprecedented market events, instability in the credit markets, and unpredictable global economies, the incentive to refinance ebbs and flows. As change becomes the new normal, the debate over fair market accounting has intensified. This discussion highlights the need for consistent fair value measurements, not just on a national level but globally. Fair value guidance is a principles-based global framework that, with few exceptions, impacts all fair value measurements in a reporting entity’s financial statements. Yet, more frequently, buyers are paying higher execution prices for legacy portfolios based on their ability to refinance or churn post acquisition. While historically taboo to churn your own portfolio, firms with preferential origination expense may find it financially advantageous to target higher Note Rate portfolios for acquisition, pay a price that partially reflects the economic benefit of the recapture, and refinance as many borrowers as economically feasible. While fair value accounting guidance is clear that firms not incorporate recapture benefits when determining fair value, it’s also incumbent on modelers to benchmark to observed trades. If observed trades reflect prices that are inclusive of recapture, then in principal, the market “at times” may in fact recognize recapture as part of a “Fair Market Value”. From a long time modeler’s viewpoint, “Fair Value”, while varied in its interpretation, should reflect value that is accessible to all. To clarify, “Cross-Sell” is not accessible to all, but the ability to refinance a borrower into a lower note rate is more readily accessible and may generate sizeable trading gains due to unprecedented Primary/Secondary spreads, not to mention a higher MSR value on the newly refinanced asset. Aside from the potential economic benefit to the borrower and lender, the perceived motivation is the underlying thought that if “We” as a firm don’t target our own customers for refinance then one of our competitors will.

Not all Fair Market Values are created equal. So what does that mean? When valuing MSRs do not fall prey to benchmarking your firms MSR value(s) to another “larger” firm, or better yet, observed transactions with more preferential economies of scale. Simply put, due to Economies of Scale, buyers tend to “Pay Up” for larger MSR portfolios, and to further compound the issue, at times, the market can be very spotty for smaller residential offerings of less than $500 million in unpaid principal balance. Buyers with more preferential economies will sometimes pass a portion of their economic benefit onto the seller in the form of bid prices that reflect their preferential economies of scale. The problem with that assumption is that larger firms, in pursuit of even more preferential economies of scale, tend to be attracted to larger swaths of servicing. Simply put, it can be as much work contractually to acquire a small portfolio as a larger one, and assuming a buyer has the capital and bandwidth to pursue larger portfolios, then smaller offerings often get overlooked by the largest servicers. Either way, smaller packages will almost always be subject to a liquidity premium in the form of higher discount rates and higher cost to service. In most but not all instances, the lower trading levels often encountered on smaller offerings are in direct relation to less preferential economies of scale among the pool of buyers that may have interest in acquiring smaller MSR offerings. Of course larger firms interested in smaller acquisition targets may do so in pursuit of wider margins as smaller offerings can sometimes trade anywhere from one-half to a full multiple lower than what a larger portfolio of equal product might transact.

Additionally, buyers can be enticed to bid on certain portfolios at a lower “marginal” cost due to the possibility that no additional employees will be needed to incrementally perform the servicing function. For instance, an additional “one” billion in principal balance associated with the MSR assets being acquired may reduce a firms total “Per Unit” cost to service, assuming no additional employees are need to perform the servicing function.

As previously mentioned, comparable trades are by far the best benchmark, but due to NDA’s, discovery of actual bid levels can be difficult to obtain. Other benchmarks may include surveys, but even reputable surveys may lack sufficient coverage of your unique portfolio characteristics, such as borrower credit profile. As such, having access to Generic Servicing Assets “GSA’s” may be beneficial to a firms benchmarking efforts. GSA’s cover a broad spectrum of the outstanding mortgage population and are benchmarked to actual transactions. Where there are large outstanding cohorts of mortgage servicing rights, a GSA is created. The GSA attributes are the aggregated attributes from the actual underlying loan collateral at the product type, coupon, and vintage year cohort level. The loan and collateral attributes of the GSA’s change annually so that the daily price changes are attributable to market factors only and not portfolio composition changes.

In the category of Fair Market Value Measurement and Disclosures, a common mistake made by many in this industry is not providing or incorporating significant data that could have a meaningful impact on the underlying value of the MSR, as described in FASB Accounting Standards Update, “Fair Value Measurement (Topic ASC 820)”, Financial Accounting Standards Board, July 2013.

iii.ASC 820-10-50-2 (e): This third requirement prescribes a greater level of disclosure regarding the valuation of Level 3 assets.

For fair value measurements categorized within Level 3 of the fair value hierarchy, a reporting entity shall provide quantitative information about the significant unobservable inputs used in the fair value measurement. A reporting entity is not required to create quantitative information to comply with this disclosure requirement if quantitative unobservable inputs are not developed by the reporting entity when measuring fair value (for example, when a reporting entity uses prices from prior transactions or third-party pricing information without adjustment). However, when providing this disclosure, “a reporting entity cannot ignore quantitative unobservable inputs that are significant to the fair value measurement and are reasonably available to the reporting entity.”

The key aspect of this disclosure is highlighted and coincidently, where, if not careful, mistakes are commonly made when valuing MSRs. A prime example might be when a firm or individual assigns a value to certain FHA MSRs while failing to recognize that within that group of MSRs there are Streamline loans, USDA loans, or 203k loans which per market benchmarks can trade at a discount. While this is only one of many examples, if you believe that your firm may be guilty, an extensive data audit review may be warranted, and actually should be received as a welcome gesture by your auditors.

Understanding One’s True Economic Value Before Buying or Selling

As someone who has been in the Mortgage business for close to 25 years, I have long been a fan of opportunistic buying and selling. Before embarking on any acquisition or sale strategy, however, it is incumbent that firms have a well-founded understanding of their true retention value before deciding on any key business strategies. For understandable reasons, FASB requires a firm hold their MSR assets on their books at Mark-to-Market levels but firms should not be overly complacent in assuming that their Fair Market and long term retention values are one and the same. For instance, how frequently do you evaluate your firm’s true cost to service? Given the complexity in determining one’s true cost, firms regularly fail to recognize whether they have an economic advantage or disadvantage relative to their industry peers. This can hold true even if your firm happens to use a specialty subservicer. For example, a subservicer may charge a very fair rate of $6.50 per loan per month or $78 per annum but that may not include other one-time or ongoing fees such as Tax Service Fees, Private Label Subservicing fees or even something as simple as 0.90 cents per loan per month in monthly billing fees. As a bank, does your firm have access to lower cost of funds than what a non-bank might recognize? For those using subservicers, who is the beneficiary of late fees and other ancillary revenue? Does your subservicer contractually retain 50% of all ancillary and late fee revenue? Do you manage your own custodial funds and if not, who ends up being the beneficiary of any potential float revenue? Other considerations may include:

-

Knowing your prepay history relative to national average or,

-

Identifying what your historical recapture rate is or,

-

Being able to recognize your historical “average gain on sale” on top of an overall awareness of any value spread between the original and newly refinanced MSR, or,

-

What cross-sell capabilities (if any) does my firm have?

After discerning your true economic benefit relative to “Fair Market”, you might decide that you have an economic advantage or disadvantage that you may incorporate into your business strategy.

Bulk Execution Options

One method of liquidating MSRs may come in the form of bulk transactions. While market conditions tend to dictate the amount of supply and demand, at some price, sellers can generally count on some level of market appetite for bulk offerings. As mentioned before, if surveyed, no two servicers will have an identical cost structure, and the same holds true of “Bulk” MSR offerings. No two portfolios are identical which fundamentally affects how or if a particular offering executes in the fair market. It almost goes without saying that sellers want to sell at the highest price possible and buyers want buy at the lowest price possible. After 20 plus years of buying, selling, and brokering MSR Bulk transactions, nothing holds truer than this. All deals, no matter the circumstance, must be a Win/Win situation for buyer and seller alike, otherwise it’s unlikely that a transaction will get consummated. For that very reason, when brokering, buying, or selling MSRs, price expectations must be “Fair” for all parties involved. Occasionally, when deals don’t trade, possible causes may be that the offered prices are less then what the seller internally has those MSR assets on their books, or perhaps the sellers expectations are consistent with how a larger portfolio might transact. What I mean is that larger transactions (usually categorized by $1 billion and higher) can execute at a premium to smaller offerings mainly due to economies of scale. Larger buyers will often seek out higher notional amounts largely because the smaller portfolios may lack the needed scale to justify the operational time necessary to effectuate a transaction. As such, the market for smaller transactions (usually categorized by less than $500 million) may sometimes attract fewer bidders and will generally trade at a higher Cost to Service to compensate for reduced economies of scale and a higher discount rate or OAS. This may account for reduced liquidity and entice larger servicers, who may still bid based on their ability, to earn wider margins.

- While not all rejoice in the idea of paying a third party to broker a portfolio of MSRs, it can be money well spent. For example, knowing the nuances of how portfolios trade and what buyers are looking for can significantly increase not only the number of interested buyers but ultimately the execution level. Case in point, it may be possible to entice more or larger buyers by limiting the number of investors in any given transaction. Larger buyers may also be interested in a “Flow” trailer, meaning a firm sells a bulk portfolio to be followed by a best efforts dollar amount to be delivered on a monthly or quarterly basis for a contractual period of time following the initial bulk transaction. It’s also critical that buyers and sellers alike be well versed in what is and what is not acceptable when negotiating purchase and sale agreements. For instance, a typical Rep and Warrants may nullify a seller’s ability to obtain sale treatment. To avoid scenarios like that, at MIAC I personally review every single Purchase and Sale agreement word by word to make sure both buyer and seller are fairly represented. This oversight can protect the seller’s best interest and can ensure buyers that their contractual terms are not only competitive but also representative of “Fair Market”. After all, who sees more Letters of Intent then a firm that is accustomed to regularly brokering MSR portfolios? Last but not least, buyers and sellers alike can sometimes benefit from the support that a professional broker might supply. For instance, a sample timeline for a Bulk MSR Servicing Transaction may look something like this:

Stage One

- MIAC will consult directly with Seller to evaluate business strategy.

- Seller provides tape to MIAC for initial review.

- Pending initial review MIAC may request additional data that may lend support to a stronger execution.

- If applicable, MIAC produces sale select that best supports Seller’s business strategy.

- MIAC begins preliminary discussions with known Buyers for similar product. The goal is to produce a select that first and foremost captures the Seller’s requirements yet also invokes buyer interest.

- Pending Seller’s approval, MIAC prepares the sale offering.

Depending on the complexity of the proposed transaction, Stage One can take approximately 2 weeks from initial consultation to finalization of the sale offering.

Stage Two

- Offering is presented to mass market and/or known potential Buyers.

- Offering date is negotiable but will typically be 7-10 business days from initial offer date.

- Buyer submits LOI (Letter of Intent) with a 24 to 48 hour acceptance period.

- Seller either accepts, rejects, or attempts to further negotiate proposed purchase price. Negotiation can add 24 to 48 hours and MIAC will assist in those negotiation efforts.

Stage Two with an interested Buyer can last 2-3 weeks before final LOI is signed. More distressed deals can take longer depending on the Buyer’s level of expertise.

Stage Three

- Upon execution of the LOI, Seller submits the necessary investor(s) form requesting transfer approval. For FNMA the application form number is 629. For Freddie Mac the application form number is 981. It is prudent to submit early due to a 60 day investor approval time frame.

- Pending a satisfactory review of Seller’s financials and loan files, the Buyer submits a Purchase and Sale (P&S) Agreement for Seller execution. The LOI should have contained all financial related data and both Buyer and Seller must agree on all other sale related items and timelines.

- In addition to a review of the Seller’s financial stability, the Buyer will most likely perform either an on-site or off-site due diligence review of a predetermined sample of the sale portfolio.

- Pending successful execution of P&S agreement the Seller can expect to receive 70% to 90% of the sale proceeds on the agreed upon sale date.

Buyer and Seller should plan on a Stage Three timeline of approximately 45 days from the initial signing of the LOI to final execution of the P&S agreement.

Stage Four

The final stage includes transfer of the servicing and loan files and is governed by predetermined transfer guidelines between Buyer and Seller. Depending on the terms of the deal, a separate subservicing agreement between Buyer and Seller should fully address the obligations of both parties to cover the time period between sale and transfer date. It is entirely up to the Buyer and Seller regarding the time delay between sale and transfer date. The one caveat is that any purchase, sale, and transfer agreement must receive agency or investor approval and must allow for certain bylaws which mandate that borrowers be notified 15 days in advance of the pending transfer.

A typical timeframe between sale and transfer date can be 60 to 90 days but can vary in either direction depending on the requirements of both Buyer and Seller.

An alternative option to Bulk Transactions may be a “Best Efforts” Non-Bifurcated Co-Issue deal which in recent years has grown in popularity among both buyers and sellers. To clarify, Non-Bifurcation refers to Seller reps and warrants which, as part of the transaction, are conveyed to the Buyer. The Non-Bifurcated Co-Issue market can be very strong with most large offerings resulting in executed transactions at attractive levels. As enticement for buyers of mostly larger MSR Bulk offerings, some flow deals are being consummated as part of, or immediately following, an initial bulk offering which on its own may be too small to attract the pool of buyers with the most preferential economies of scale. Not dissimilar from MSR Bulk offerings, large buyers often seek out larger commitments of at least $50 million per month, and preferably larger, but, thankfully, sellers continue to benefit from the ever increasing number of Non-Bifurcated Co-Issue buyers. Co-Issue flow has proven to be a valuable option for cash motivated sellers seeking to maximize their gain without the hassle of long term MSR ownership. While some buyers have tightened up their acquisition guidelines and now seek out sellers with higher Net Worth and higher volume commitments, opportunities still exist for most. Co-Issue flow can also be a lucrative option for buyers and sellers seeking longer term partnerships, not to mention the “co-issue” program assists with cash and capital management by monetizing MSR upfront while still providing the benefits of direct delivery.

Other Benefits to Non-Bifurcated Co-Issue can include:

-

Direct Sale to GSE

-

Speed of Settlement

-

Absence of Aggregator Overlays

-

Pricing Stability – MSR grids are static for 30 or more days with periodic Par Note Rate Adjustments

-

Operational Efficiency

-

Co-Issue Execution is frequently the outright Best Execution, and is often a compelling alternative to Aggregator Released or GSE Retained execution

-

Simultaneous Transfer

-

Seller assigns servicing to MSR Buyer during delivery to GSE

-

Seller reps and warrants transfer to MSR Buyer (“non-bifurcated”)

-

Seller usually avoids boarding MSR to servicing system or sub-servicer

-

Simple, straightforward deliver/settlement process with MSR Buyer

Whether engaging in Bulk or Co-Issue executions, extensive experience in pre-market analysis, Best Execution loan sale selection, bid preparation, and closing are key elements of any successful transaction. Thorough knowledge of mortgage products, coupled with expertise in collateral behavior, will ensure that execution prices are “Fair”. It is also reasonable to say that aggressive marketing of each portfolio can create a more competitive pricing environment. Last but not least, intimate knowledge Mortgage Loan Purchase and Sale Agreements, complemented with excellent negotiation skills, will ensure that both buyers and sellers alike have as seamless transaction as possible. If you feel your firm needs support in any of the aforementioned categories, professional support is highly encouraged.

Author

Mike Carnes, Managing Director, MSR Valuations Group